Memento Mori: Curiosity and Connection

Society's Enduring Fascination with Death and Disaster

The tragic story of the Titan has swept the internet, and I think I’ve read just about every opinion there is to have about it. The most interesting of these to me has been the morality scold, ‘they should leave the Titanic to rest in peace, it’s not right to disturb a grave site’. But we do this all the time, don’t we? We use churches with headstones in the floors as community spaces, we pay entry to see their architecture, all the while literally walking over graves. We can pay to do tours of cemeteries, Highgate in London for example, is one of the most popular ones.

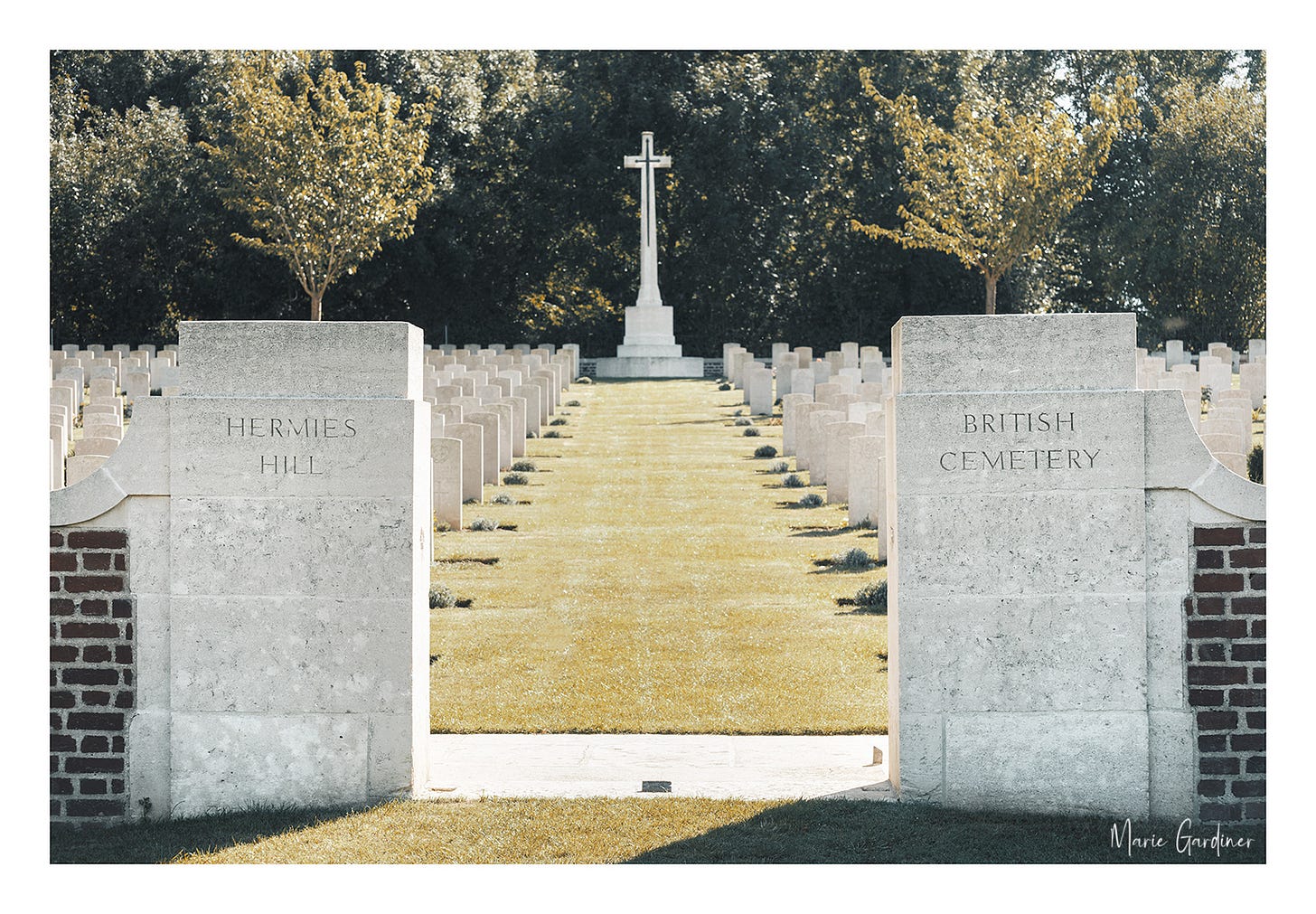

And so the next logical segue argument might be that those aren’t large-scale disasters, which then makes me think of the pilgrimages many of us make to battlefields from the First and Second World Wars, to the mass graves we visit like those of Cholera (there’s one in Sunderland, marked, but still on some scrub land) and those to sites of horrific atrocities like Holocaust concentration camps. Is education the saviour here? We visit these places to learn, to understand. Sure, and I think that’s absolutely a part of it, otherwise why go at all, right?

We can’t say for sure the people who went to see the Titanic weren’t interested in history, so that argument doesn’t really stack up either. Is it the location, then? I think this is definitely one of the things that has everyone so opinionated. If it’s ‘wrong’ to visit the Titanic in her resting place, would that change if she was in a museum? I think so. I know for a fact that I wouldn’t go to terrifying depths in a glorified tin can to see the Titanic, but I’d definitely visit a museum if she was on display, so I know it isn’t a sense of right and wrong that’s stopping me, and I don’t think the people in the submersible would be being judged in the same way if that was the case either, so then what is the difference? I think it’s two-fold.

The first issue is that parts of this exploration have been experimental and developing. That’s fine if you want to risk your own life and the law says you can do that. But to sell tickets for people to do it, this is when we start to get into the commercialisation and profit - at the risk of others - of disaster tourism. I’ve seen people exclaim how could the passengers willingly sign a waiver that mentions death several times, but think about how often we accept risk with very little thought. Every medication has a leaflet outlining all the terrible things that might happen, we accept terms and conditions to websites without reading them, we’re in an age where we think ‘yeah there’s a risk, but they have to say that don’t they?’ We get into cars and planes knowing the dangers. This is different, of course, no argument there, but I can fully understand the mindset of someone who has filed their reservations deep in their mind in that same way. If blame lies somewhere, it’s that people were allowed to create something fundamentally unsafe and unregulated, and then to commercialise that to people with perhaps more money than sense. And money does come into this, because quite often, people and businesses with vast amounts of wealth think they’re simply above the standards that others are held to, and no doubt hubris played its part in this tragedy. For confirmation of this we only have to look at how it was reported: explorers rather than tourists, bravery rather than unnecessary risk; then compare that to how the migrant boat sinking off Greece was covered.

So this brings us to the second issue: Instagramification. If not an interest in learning more, why else are we there? To say we were. To do something that few other people can do, perhaps, to get a photograph, to tell a story. We’ve seen recently the reports of young people taking grinning selfies outside of the gates of Auschwitz. ‘Why would they do that?’ Part of this is a lack of education, and those are systemic faults. Some people have a desire to visit these sites because they’ve seen them online, without any real understanding of the place they are, of what it means both to individuals and to us collectively, our history.

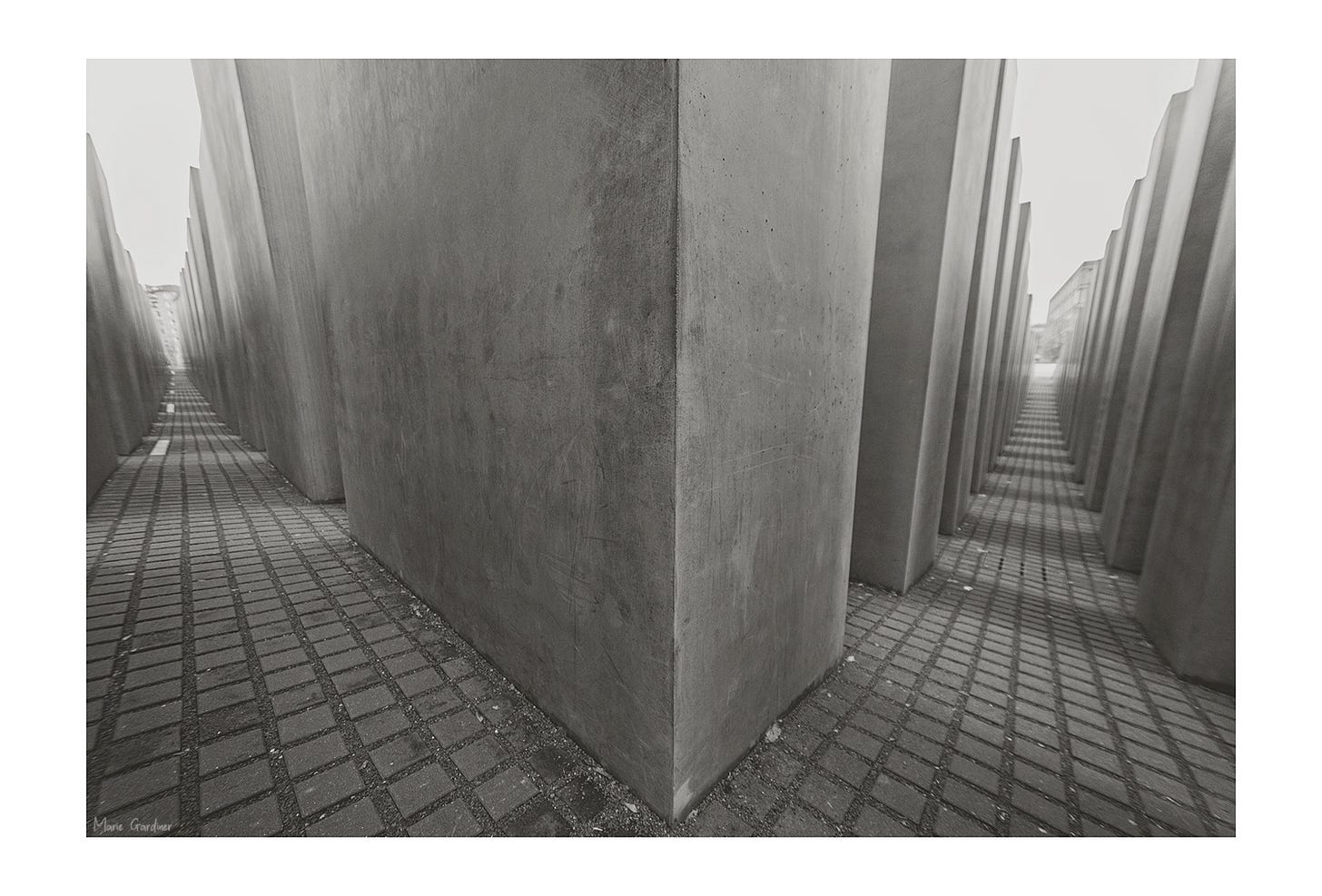

I read that someone couldn’t visit the 9/11 memorial in New York because they can’t stand people around the memorial taking pictures and laughing and so on. It’s only been two decades, that event is still so raw and very much in the living memory of most of us, so I can understand that. However, I also think that memorials like the one for 9/11, the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin, the beaches and their various memorials at Normandy, just to name a few, are still part of life. They’re in the midst of cities or holiday sites, ones not just since the events they commemorate, but how they were before. I think with places like this - unlike the more isolated and hallowed sites of concentration camps - are a testament to the endurance and resilience of people, that they can have their place in the communities they affect, can be visited and acknowledged, but also have life around them. I remember reading somewhere that the designer of Berlin’s Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe is supposed to make visitors feel uneasy and confused, but that also it would be a place that children ran through, where people would stop and eat, and look and think. If all memorials are to be places where people can’t be, then are people put off visiting them? If so, what’s their purpose? We want people to visit, to see, and hopefully to learn. There should be respect, no doubt, but again I would say the lack of that is mostly down to ignorance, and for those who’ve grown up only knowing it, the internet and its desperate desire for engagement over, well, over absolutely anything, but certainly over knowledge and understanding.

Another thing that I often think about when it comes to discussions around this subject, is the strange relationship we have with death. That people who don’t study history or other cultures will attribute how we are now about it, to those in the past. I saw a quote along the lines of ‘the people in the Titanic would have been horrified to have visitors to their graves some 100 years later’. Would they? The Titanic sank in 1912 and many passengers would have been adults through the Victorian era, where people were fascinated by death. They wrote extensively about death, embraced Memento Mori, the practice of reflecting on death, made jewellery and other trinkets, they took portraits of the dead as tokens. Grave sites would be made ornate and beautiful, visited regularly, sometimes even with a picnic. We have not always been so squeamish and removed from the dead, and other cultures still aren’t. There’s a wonderful book called From Here to Eternity - Traveling the World to Find the Good Death by Caitlin Doughty that really opened my eyes to the way other cultures treat death and how that’s in such stark contrast to how we feel about it.

It’s easy for us to sit here and say ‘no way would you have got me miles under the sea in a tin can,’ but it’s not as simple to reflect on why someone would want to visit the site of the Titanic, or any other site of tragedy for that matter, and whether it’s the right thing to do. I’ve visited First and Second World War battlefields and cemeteries, I’ve visited the landing sites of Normandy from D-Day, I’ve been to holocaust memorials, a concentration camp, to the sites of mass disasters and mass graves. Is that disaster tourism? Or is it not quite as straightforward as that? I think we all have a curiosity about death, about the fragility of life, and about our own mortality. Many of us have an interest in the history that surrounds those events, either to give us context, or to learn from them so that we don’t repeat our mistakes. We all have a duty to behave appropriately at these sites though, and that comes with learning why we’re there in the first place.

The Titanic has a particular draw on us, in some ways it’s the tabloid disaster event, it’s been romanticised in films, particularly the popularity of the one by James Cameron. My Heart Will Go On from the Titanic soundtrack was supposedly played in the submersible on the way down. It’s a cheapening of it’s very real and important history. There is nothing to be learned (I’m strictly talking about average tourists, not scientists) from seeing the wreck of the Titanic other than an exciting, almost Disneyfication of a very serious disaster where a lot of people died, and I think that’s the core issue with this whole thing: context. In a museum, Titanic would be surrounded by interpretations, explanations… context. Seen as it was, though undoubtedly fascinating to go to there was nothing to be gained. And as it turned out, tragically, everything to lose.

I grew up in NYC, lived there for the first 30 years of my life...could have lost my brother to 9/11 if he was not late to work. As of 2016, the last time I was in the city, I have not been to the 9/11 memorial. It's...too much for me.

Hi Marie, where's the Cholera Memorial in/near Sunderland? I was in Mowbray Park, a couple of days ago, which was built as a result of the cholera epidemic, after recommendation by the subsequent enquiry, yet there seems no memorial there to the epidemic itself?